I’ve been working on an internal BCcampus project to set up and configure Kaltura MediaSpace for our internal use. We have a number of use cases, not the least of which are providing a central hosting space for videos created as part of a grant associated with the BC Open Textbook Project. Since these videos will be openly licensed (as is everything we create at BCcampus), I want there to be a visible Creative Commons license with each video to let users know the terms of usage for each video.

Out of the box, MediaSpace has a lot of functionality, but the ability to apply a Creative Commons license to a video is not one of them. So, with a bit of consultation with my colleague (and knower of all Kaltura secrets) Jordi Hernandez at UBC, I was able to add a basic CC license field to the videos we host in Mediaspace.

It is actually a pretty straightforward 2 step process. First, you need to create custom metadata fields in the Kaltura Management Console (KMC), then you have to enable the fields in the Kaltura Mediaspace administration console.

I am using an OnPrem service of Kaltura. The MediaSpace instance I am working on is 5.38.07.

Create Custom Fields in the KMC

After logging into the KMC, I went to Settings > Custom Data. This is where I will set up the custom data scheme and define the CC licenses. Click Add New Schema to create a new Creative Commons Metadata Schema. Give your Schema a name, description and a system name. The system name should be one word and short. We want each video to be able to have their own CC license, so we want this metadata schema to apply to Entries and not Categories.

Once you have the Schema set up, you will want to add the actual licenses as field values. Choose Add field and enter in the different CC licenses that you want to make available to your users. These are the options they will see when they upload a new video, and what people who view the video will see on the screen associated with the video. I chose to make my list a Text Select List so that it would appear as a drop down menu for the person uploading the video.

One nice feature of the custom metadata schemas in Kaltura is that you can enable these items to be searched for in the built in search engine. So, with CC licensed material, someone could come to our video portal site and search for nothing but CC0 videos in our collection. I haven’t explored this fully yet, but it does seem to work at a granular level. Which is both good and bad. Good if you want to search for a specific type of CC licensed content in our collection, like a CC0 or CC-BY video. But not so great if you wanted to search for all CC licensed videos regardless of flavour.

Once that is done, the Schema is setup and we can now slip over to MediaSpace to apply it.

Add the custom fields to the upload form in MediaSpace

I logged into the MediaSpace admin console. The area we want to play in is called Customdata. It may appear with a line through it in your admin console. That just means that the module has not been activated.

Go into the Customdata module and make sure it is enabled. In the profileid field, you should be able to find the custom metadata schema that you just created in the KMC. Choose that. You can also make the field a required field and, if you wish, enable the showInSearchResults field to enable the search index.

That’s it. Save the changes and you now have added a custom CC license field to your videos. When someone uploads a video to MediaSpace, they will have an additional field in a dropdown menu that they can choose a CC license to apply to the video.

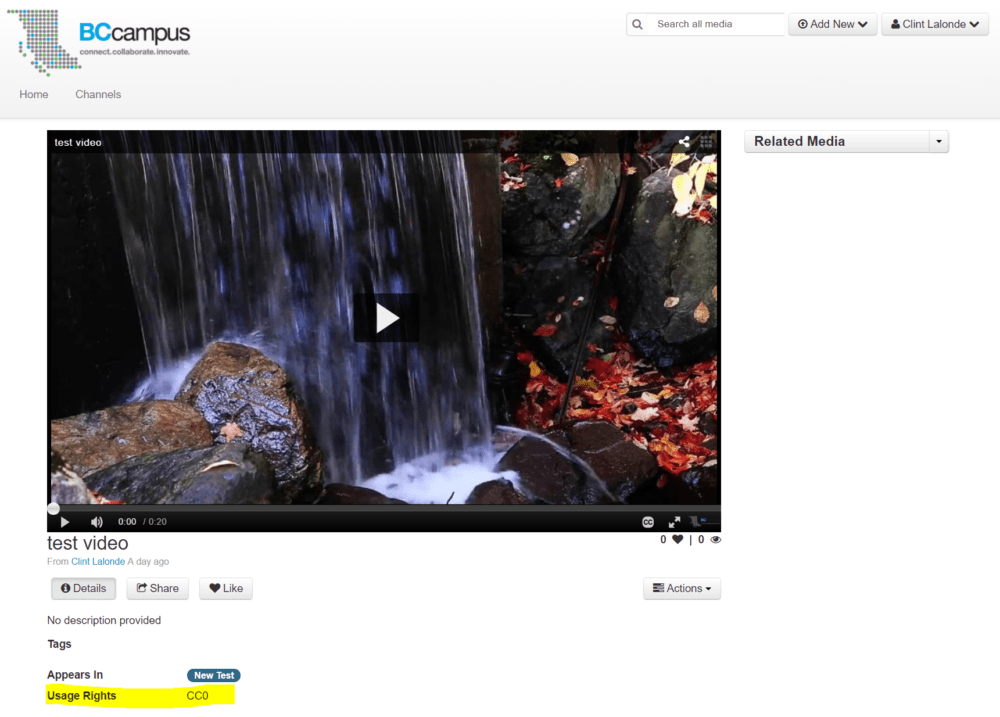

And, when people come to view the video in the MediaSpace site, they will see that the video is licensed with a Creative Commons license.

Now when we upload a video to our MediaSpace site, we can assign it a Creative Commons license that people can see.

Good first step

For me, this is a good first step that gives us the option to apply a visual marker to the video in MediaSpace. However, what would be great (and I am not sure that this can be done) would be to have that CC license metadata embedded in the page in the correct metadata format for CC licenses. This would ensure that it would be found in search engines when people search for CC licensed content.

The second improvement would be to somehow embed that CC license metadata right in the video so that if some were to take a copy of this video, the original license information would go along with the actual video when they downloaded it. Doubt that is possible, but that would be a great feature for organizations like ours that produce a lot of openly licensed content.

Finally, I think that it might be a good idea to add a visual bumper as part of the video that would spell out the CC license. It is what we currently do with our videos, and is good practice to help make it clear that the content is openly licensed.

Photo: CC Stickers by Kristina Alexanderson CC-BY

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png)